History of Elections

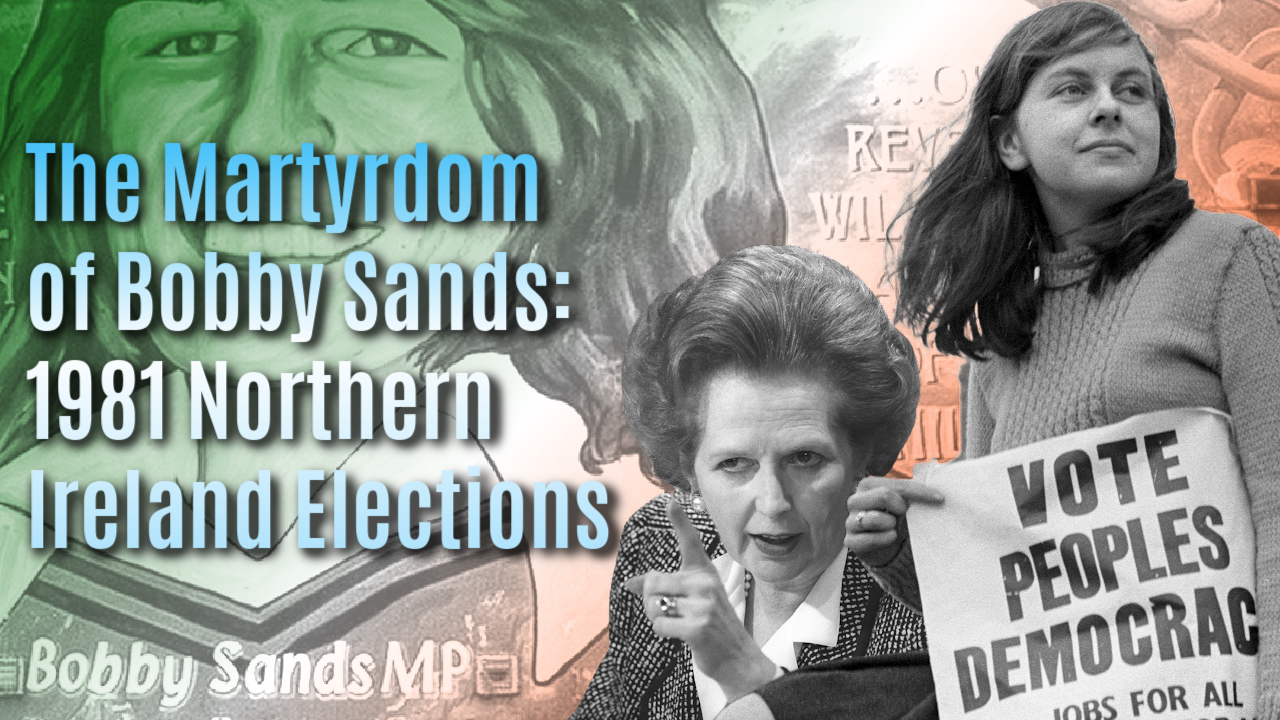

Episode ThreeThe Martyrdom of Bobby Sands:1981 Northern Ireland Election

Episode ThreeThe Martyrdom of Bobby Sands:1981 Northern Ireland Election

Elections are sometimes the battlefield upon which other struggles are fought. The appointment of Bobby Sands to the U.K. Parliament while he was dying from a hunger strike in a prison in Northern Ireland shows that political success or failure can be less about the office at stake than the communication of grievances or the galvanization of a movement.

Transcript*

"Too long a sacrifice can make a stone of the heart"

-– from Easter, 1916 by William Butler Yeats

April 9, 1981. Northern Ireland.

Bobby Sands, a twenty-six year old Irish militant serving a 14-year prison sentence, has just won a seat in the British Parliament.

With an 81 percent turnout, he has defeated a Unionist, establishment-backed candidate with 51 percent of the popular vote.

He has become the first volunteer from the Irish Republican Army, or IRA, to win a seat in Westminster.

Sands was not there to hear the results, nor did he celebrate his historic win. "In my position," he was heard saying after the radio announced the election results, "you can't afford to be optimistic,".

Sands' use of the phrase "in my position" grossly oversimplifies what was certainly one of the most dire set of circumstances any electoral candidate has ever been in.

For at the time, Bobby Sands was lying in a prison cell in the infamous H-Block of Her Majesty's Prison Maze in Northern Ireland.

He had been on hunger strike for 41 consecutive days and could barely move – much less generate any excitement over his win. Within a few days, he would lose his vision. In less than two weeks, he would be dead – the first of 10 men to starve themselves to death in protest against the policies of the British in Northern Ireland.

Although the government of Margaret Thatcher in London tried to dismiss its significance, Sands' electoral victory was one of the most pivotal moments in the almost half-century-long conflict in Northern Ireland which was known then, as now, as the Troubles.

The hunger strike begun by Sands and nine fellow-inmates was a planned and coordinated action to protest their treatment by the British authorities. But his campaign for the British legislature was very much the result of an unexpected opportunity created by the sudden death of a sitting MP named Frank Maguire.

The vacancy left by Maguire's death was to be filled in a special by-election called in the UK constituency of Fermanagh and South Tyrone in Northern Ireland. A coalition group called the Anti H-Block Committee put forward Sands as a candidate for the newly open seat.

The campaign to elect Sands together with his highly publicized hunger strike became a rallying point around which the Irish Republican movement coalesced, and it served to reshape the narrative with which the Troubles had been described by the British. Sands' selfless sacrifice made it harder and harder to dismiss the actions of the Irish liberation movement as "terrorism" or mere "criminal" behavior, as the British government tried to portray them. The Troubles came to be seen more and more as a political conflict between forces of oppression and those seeking basic human rights.

The slogan for Sands' successful campaign was, "His life is in your hands, vote Bobby Sands."

Sands perished on the sixty sixth day of his agonizing hunger strike.

More than 100,000 people in Northern Ireland – a region with a population of 600,000 Catholics – would attend his funeral.

And, despite the changes to the struggle brought by Sands' death, the Troubles in Northern Ireland would continue for almost two more decades.

For this episode of the History of Elections podcast, I want to explore the motives and accomplishments of a decidedly unconventional campaign to elect a dying man to political office. I will, of course, try to provide the context for this extraordinary movement.

We will see, for example, how the campaign to elect Sands mobilized Republican Catholics to reassess their practice of non-participation in the electoral process and to vote for the first time. Before Sands, the strategy of the Republican movement was to boycott elections which they deemed illegitimate. After his victory and death, the Republican Party Sinn Fein would change their strategy and run elections everywhere they could. Over time, they would slowly build power and legitimacy. Sands' election was a turning point that would place Sinn Fein on a trajectory which would make them the most popular political party in Northern Ireland, according to the latest polls (in 2022) .

But I also want to try to answer a very difficult and perhaps somewhat inflammatory question: to what degree did Sands' sacrifice have a positive impact for his cause? And why?

From the conventional perspective, his campaign did not succeed – by at least two measures: If the goal of an election is to send a representative to govern on behalf of his constituency, well, that of course did not happen as he could not even physically leave the H Block prison.

But that, of course, was not the goal of Sands or the Anti H-Block Committee. They were utilizing electoral politics for publicity, and not to have Sands as an actual representative that would serve his constituency in Westminster.

So, what about Sands goal for him and his fellow nine inmates to be treated as political prisoners?

After a four-month period that saw 10 men, all in their twenties, perish one by one from starvation, the British government refused to budge. And Prime Minister Thatcher continued to characterize them as criminals.

What's more, while the hunger strikers had engaged in the ultimate form of non-violent resistance, their deaths were followed by an increase in violence and killings by the IRA, and many Catholics grew doubtful of believing in the usefulness of non-violent resistance.

So that's the short term result: a failure to have their demands recognized and an aggravation of the violence.

But what about the long-term? Didn't the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 bring peace to Northern Ireland? And wasn't the hunger strike a major part of the struggle that eventually led to the end of the Troubles?

Sands and his comrades landed in prison for their role in the battle to free Ireland from British rule. Judged from that ultimate objective, the Good Friday Agreement may have ended years of bloodshed, but it did not unite the two Irelands. In other words, the Troubles did not end in a decisive victory for the cause to which Sands had dedicated his life.

Whether you are an Irish nationalist or a listener who may just be hearing about Bobby Sands for the first time, it is human nature to want to believe that his courageous and selfless sacrifice was not in vain – that its goals were achieved – that some lasting good came from it.

But extreme forms of non-violent civil disobedience only sometimes result in success.

To use a famous example, Mohamed Bouzazizi, the Tunisian protestor who set himself on fire in 2010, triggered a wave of revolutions known as the Arab Spring across two continents.

Now compare that example with Wynn Bruce, a climate activist who also set himself on fire in April 2022 in front of the U.S. Supreme Court.

While Mohammed Bouzazizi is now memorialized all over Tunisia for the role his sacrifice played in his country's movement toward democracy, no one remembers Wynn Bruce. Despite his sacrifice and the importance of the issue for which he died, Bruce's death has not resulted in any mass mobilization or tangible gains. It has largely gone unnoticed. No matter how much we might honor Wynn Bruce, we must conclude that his action may not have been worth it – that he may have died in vain.

So in this episode, we will take a closer look at Bobby Sands' campaign and death and we will seek an answer an uncomfortable question: Did Bobby Sands and the nine other hunger strikers who followed him suffer and die in vain?

I hope by the end, we will not only learn of the story of the historic Bobby Sands campaign. But also understand when, why, and how campaigns centering on extreme forms of civil disobedience succeed. By examining the implications of his story within a broader context, we can perhaps learn more about the advantages and limits of civil disobedience and the dynamic created when such acts merge with a radical electoral campaign.

Part 1: Bloody Sunday

Of course, we cannot appreciate the story of Bobby Sands without understanding the historical background.

But a good place to begin is January 31st, 1972.

On that day, Bernadette Devlin, a Catholic MP representing Northern Ireland's Mid-Ulster constituency, was flying back to London for an emergency session in Westminster.

The day before, Devlin had witnessed British Paratroopers gunning down 14 unarmed Catholic protestors in the city of Derry. The slaughter became known as Bloody Sunday.

As the only member of Parliament to have witnessed the incident, she knew that the future of Northern Ireland rested on her shoulders. She had to tell her fellow legislators and, indeed, the rest of the world, how a peaceful demonstration for voting rights (as well as an end to job and housing discrimination) was met by bullets from the 1st Battalion Parachute Regiment.

This same regiment had been responsible for killing at least nine civilians five months earlier. But Devlin knew that this time was different. The British had gone too far on Bloody Sunday and had perhaps pushed the Catholic residents of Northern Ireland to the breaking point.

To bear witness to Bloody Sunday would have been a daunting responsibility for anyone, but perhaps especially for Devlin, who, at the time, was not only one of the very few women in the UK Parliament – she was also its youngest member.

Still, Devlin may have had reason to be confident.

Elected in 1969, as a socialist seeking to unite Catholics and Protestants through shared working class issues, Devlin was the youngest woman ever seated in the House of Commons. Yet her first speech, delivered on her 22nd birthday, was praised by one journalist as "The finest Maiden Speech since [Benjamin] Disraeli" in 1837.

Devlin was also no stranger to violence, having built barricades alongside other Catholics during the Battle of the Bogside in the summer of 1969. This three-day period of unrest was an important catalyst for the start of the decades-long Troubles. Devlin was there and saw firsthand how the police terrorized the Catholic population.

In another dangerous brush with violence, a peaceful parade that Devlin had organized was attacked by Unionist vigilantes as they marched from Belfast to Derry. She barely escaped with her life.

As she raced back to Westminster to tell the world what had happened on Bloody Sunday, it was all she could do to keep herself together.

It may come as no surprise that Devlin's fellow MPs in the almost all-boys club of Westminster were less eager to hear her account of the massacre than Devlin was to tell it.

Having been convicted and sentenced to serve a short term in jail for her role in the Battle of the Bogside, Devlin had the reputation of a troublemaker. Among her supporters back home, she was hailed as Northern Ireland's Joan of Arc. For the English, as you can probably guess, she was about as popular as the original Joan of Arc.

Devlin knew that when she rose to speak, she would be completely alone in Westminster, with no one to support her, and with the Tory backed House Speaker refusing to give her time to speak.

But what happened that day in Parliament was nevertheless very revealing and bears being told in detail.

The so-called debate for the emergency session opened with remarks from the Conservative Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling who immediately made the false claim that the British Paratroopers had acted in self-defense after coming under fire from the IRA.

Devlin rose several times to refute this version of events. When she was ignored, she raised a point of order. "Is it in order," she asked, "for the Minister to get up in this House unchallenged and tell lies?"

The House Speaker chastised "The Honorable Lady for Mid-Ulster," saying that she "must not call a Member of Parliament a liar and must withdraw her statement."

"I will withdraw the word but not the sentiment." Devlin hit back, "But I assert my right as the only eye-witness to speak." Although Devlin was absolutely correct in her understanding of Parliamentary practice, the House Speaker tried once again to shut her down:

"The Honorable Lady for Mid-Ulster has no rights other than those given to her by the Speaker" he said smugly.

Devlin then corrected the Tory House Speaker, who apparently was under the mistaken impression that it was wise for an Englishman to tell an Irish woman she had no rights.

"The Honorable Lady for Mid-Ulster," she said, referring to herself, "has whatever rights in this House it is within her power to exert!"

If the House speaker was determined not to let her speak, Devlin could resort to another form of self-expression:

Rising from her seat, she strode across the floor of House of Commons and slapped the Home Secretary Reginald Maudling in the face.

Devlin was, subsequently vilified by the British press for being "unladylike." And about two years later, she would lose her seat in Parliament. But Devlin did not regret giving up her career in government in that one moment of rage. Years later she would say that her only regret was that she "didn't hit [Maudling] hard enough."

As I mentioned a moment ago, Devlin's slap came at a pivotal point in the Troubles, and it was perfectly consistent with the changes taking place among a great many of Northern Ireland's Catholics, who, after Bloody Sunday, began to question the efficacy of their largely non-violent resistance movement.

Just as Devlin had reached a personal breaking point on the floor of the House of Commons, Northern Irish Catholics were collectively reaching their own.

One of the witnesses to Bloody Sunday was a priest named Father Edward Daly. There is a famous photo of him escorting an injured and bloodied protestor. Reflecting on the changes in people's thinking brought by that day, Father Daly remarked:

"A lot of the younger people in Derry who may have been more pacifist became quite militant as a result of it. People who were there on that day and who saw what happened was absolutely enraged by it and just wanted to seek some kind of revenge for it. In later years many young people I visited in prison told me quite explicitly that they would never have become involved in the IRA but for what they witnessed, and heard of happening, on Bloody Sunday." (p.89)

Some of the hearts that turned to stone on Bloody Sunday resorted to violence.

Before the year was out, the IRA would take the fight to the British and carry out its first bombing on the British mainland since the start of the Troubles.

Part 2: The Blanket Men and Lost Opportunities

The nature of the conflict changed. What had begun as a peaceful civil rights movement was radically transformed, as violent and increasingly sensational attacks became more popular with the resistance. In the process, the movement – indeed the very cause for which Northern Ireland's Catholics were fighting – was successfully rebranded by British propaganda. Sporadic and shocking attacks by the IRA enabled the British government shrewdly to recast the Troubles in Northern Ireland as nothing more than the barbaric activities of a small minority of violent criminals. The Troubles were no longer about civil or human rights. It was a matter of lawlessness and disorderly troublemakers.

Pro-republican figures like Bernadette Devlin toured America and made TV appearances in order to remind international audiences of their cause, but British propaganda proved to be too formidable.

One of the important responses of the British government to the rise in IRA attacks was the elimination of something called Special Category Status. This change, which was announced in 1976, meant that anyone whom the British deemed a "terrorist" would be seen not as a political prisoner but as a common criminal, and that person would be treated accordingly.

This may seem like a trivial matter of semantics. But, as we will see, it became a critical flashpoint for the prisoner protests which culminated in the hunger strikes of 1981.

Gerry Adams of the Republican political party Sinn Fein described the new policy like this:

"British propaganda .. [was] attempt[ing] to establish that the military and political struggle that had been going on … in the [North] had ceased to exist, and that the British were only faced with the conspiracy of a few criminals." (Ross, p.20)

Though Adams recognized the meaning of the new policy, his party, Sinn Fein, did not immediately recognize it as the galvanizing issue it eventually became.

One person who did, however, was Bernadette Devlin.

She, along with a fellow founding member of the socialist organization People's Democracy, approached Sinn Fein with a proposal to run a joint campaign to defend political status for prisoners. Sinn Fein rebuffed the idea. (Ross, p.24)

However, Sinn Fein's initial disinterest in organizing a campaign around the issue of political status was a moot point by September of 1976.

It was then that imprisoned IRA volunteer Kieran Nugent staged the first so-called "blanket protest." To draw attention to the question of status, Nugent refused to wear a prison uniform and wrapped himself up in a blanket as his only clothing.

While groups outside the prison walls continued to temporize, by 1977, as many as 200 prisoners had taken Nugent's cue, joining either a blanket or "no wash" protest (or both?). (Ross, p.32)

By January of 1978, as prisoner-led protests escalated, organizers outside of the prisons finally got together for a conference with the newly formed Anti H-Block Committee.

They came from a diverse group of political parties — from republicans in Sinn Fein, moderates in the Social Democratic Labour Party, and even radical Marxists in Popular Democracy. After some factional disagreements, they put their differences aside to support a campaign for the men and women languishing in British-run prisons.

While there was consensus that something had to be done on the question of political status, these groups struggled to agree on the best tactics to deploy.

One key sticking point was the option to advance the prisoners' cause through electoral politics.

With an upcoming election for the European Parliament in 1979 (the first ever in which residents of Northern Ireland would vote), some groups believed that this was the best opportunity to call attention to the issue of political status for prisoners.

It would bypass Westminster and take the prisoners' cause directly to an international legislative body. Sinn Fein, which had long disdained the political process, was not willing to go along.

But that did not stop (our old friend?) Bernadette Devlin from running as an independent candidate with the singular purpose of calling attention to the plight of the Irish prisoners.

Although she performed quite well, Devlin didn't win, largely due to the lack of unified support from her own side.

Sinn Fein, not surprisingly, criticized Devlin and claimed that her run was based on "opportunism." (Ross, p.59)

As we will see, Devlin would be proved right. And, thanks in part to her initiative, Sinn Fein would eventually re-think their traditional tactic of abstaining from participation in any British institution. This would be one of the most decisive policy changes for this influential group.

In addition to Devlin's example, Sinn Fein could also look to a case in which the stubborn, albeit principled policy of abstentionism backfired at great cost.

On March 28, 1979, UK Labour Prime Minister James Callaghan faced a vote of no confidence in Parliament. He lost by the narrowest of margins: just one vote. (The final tally was 311 to 310.)

Now, you have to understand that the Labour Party was relatively more disposed than any other major party to the cause of the Catholics in Northern Ireland as many of their problems were rooted in government policies that adversely affected the working class.

It is true that the Special Status Category had been eliminated under a Labour-led government. But Labour was far and away the lesser of evils when it came to sympathy for Irish Catholics among leading British parties.

The defeat of a Prime Minister from Labour was, consequently, a major setback. It ushered in the eleven-year leadership of Margaret Thatcher, whose uncompromising style of governing earned her the nickname the "Iron Lady."

Historians look back at this moment as the end of "Old Labour" which would not take power again until the neoliberal centrist "New Labour" under Tony Blair 18 years later.

As I mentioned, this major turning point in 20th Century British politics might never have happened if just one minister voted differently.

As it so happens, two MPs who were decidedly sympathetic to the cause of Catholic civil rights in Northern Ireland chose, as was their practice, to abstain.

These men were social democrat Gerry Fitt and the independent Frank Maguire.

You will remember Maguire as the MP whose death would open up a seat in Bobby Sands' constituency.

In what is considered one of the most dramatic events in Westminster history, the staunch abstentionist Maguire travelled to Westminster just to abstain in person.

To be fair, the Conservatives certainly got a boost when, just one month before the election of Margaret Thatcher, a fellow Conservative MP was assassinated by the Irish National Liberation Army.

But the stubborn refusal of pro-Catholic members to vote when it most counted was clearly a crucial mistake for the movement in Northern Ireland. Callaghan's Labour government was succeeded by a ruthless Tory government. And Thatcher came into No.10 Downing Street with a narrow mandate to crack down on Northern Ireland and to concede, in her words: "not an inch."

As American civil rights leader Kwame Ture (Stokley Carmichael) famously stated: "In order for nonviolence to work, your opponent must have a conscience."

In the bloodiest year of the Troubles in 1971, Labour Party leader Harald Wilson – a once-and-future prime minister – put forward a scheme that would, over a long period, allow for an eventual unification of Ireland. Wilson, of course, did not follow through on uniting the two Irelands when he briefly served again as prime minister from 1974-1976. Still, his proposal suggested an opening – that Labour could perhaps be moved if enough pressure were exerted.

Labour, for all its shortcomings, at least, had a conscience.

But Thatcher, it must be said, had no conscience. She bore her reputation as the "Iron Lady" proudly.

Her adamant refusal to be moved by non-violent resistance would lead to more death as the anti-British movement was forced to use other means in its struggle.

So we turn now to the origins of the Hunger Strikes.

The National Anti H-Block / Armagh Committee had been formed in order to advocate, from the outside, for the men and women prisoners incarcerated, respectively, in. "H block Maze" and Armagh.

By the autumn of 1980, four years into the blanket protests (with no results), the idea of a hunger strike began circulating among the prisoners of H-Block.

The prisoners possessed a keen sense of history and how it could be used to their advantage. They were well aware of the death of Terence MacSwiney, the Mayor of Cork who had been imprisoned by the British during the Irish War of Independence earlier in the century. MacSwiney's death after a 74-day hunger strike gained international attention for the Irish cause.

Perhaps a new hunger strike, 60 years after MacSwiney's, could do the same.

Of course, the prisoners also understood the powerful chord their death by hunger would strike among the Irish people in whose minds the memory of the Great Famine was still vivid.

This 19th century genocide, brought on by British negligence and unfair trade laws, resulted in a million Irish deaths – in a country of barely a few million. It lead to massive emigration and forever changed the history of Ireland. Irish people everywhere, at home and abroad, would surely understand the what it means to starve to death at the hands of the British.

Part 3: Bobby Sands MP

For understandable reasons, the members of the National Anti H-Block / Armagh Committee were not enthusiastic about the idea of a hunger strike. They did not want to endorse a plan that would put the prisoners through a prolonged and agonizing death. Sinn Fein wanted to avoid a hunger strike at all costs. (Ross, p..92)

But the prisoners felt they had no other option. The blanket protest had not worked. It was time to up the stakes.

For their supporters outside the prison, the hunger strike was a horrifying prospect, but the need to show solidarity was equally acute.

On October 26th, 1980, Bernadette Devlin led a march of 17,000 protestors in Belfast in a strong show of support for the political prisoners. After 11 years of stagnation, the non-violent civil rights movement in Northern Ireland was showing new signs of life. It was an emotional event. A journalist who was there noted the tears of joy that ran down Devlin's face.

The morning after the march, seven IRA volunteers imprisoned in H block announced the start of a hunger strike.

In another nod to history, the prisoners opted for seven hunger strikers because this was same as the number of signatories to the Easter Proclamation of 1916 which triggered the Irish War of Independence. (Ross, p.96)

The number seven created a symbolic link between the men in H Block and their patriotic forebears.

On December 1st, the hunger strike by male prisoners of H Block was joined by three female IRA volunteers in the Armagh women's prison. (Ross, p.101)

The hunger strike begun in October of 1980 ended on December 18th after fifty three days. No one died.

The decision to call off the strikes came after a nebulous offer from the British government which the prisoners thought might eventually lead to political status.

But in the end, it was merely a bluff. Thatcher ended up conceding to nothing – true to her pledge not to give an inch.

Having failed in their first attempt, the prisoners now planned a second wave of hunger strikes.

And this one would be different. Rather than have several prisoners strike simultaneously, the new plan was for them to begin their hunger strikes in succession, one at a time. This would prolong the duration of the collective strike in order to keep attention fixed on their protest.

The second wave of strikes began on March 1, 1981 with with 26 year old IRA volunteer Bobby Sands.

While Bobby Sands is the eponymous protagonist of this episode of the History of Elections Podcast, and while his name is well known to anyone familiar with modern Irish history, the truth is that Bobby Sands is bit of a mystery. And we do not know much about his life. Viewers of the video version of this episode have no doubt noticed that I use the same photo of Sands. This is because there simply aren't many photos of him.

By 1981, when he was serving a 14-year prison sentence for illegal weapon's possession, Sands had already spent a quarter of his young life behind bars.

What we know of Bobby Sands must be pieced together from different sources. Much of the most illuminating and moving of these are his own writings, which include articles he wrote under the pen-name "Marcella," as well as some poems he wrote in prison before his death.

At the end of this podcast, I will return to one of these poems, as it sheds light on the question we are seeking to answer – namely, did Bobby Sands die in vain?

For now, it is enough to note that there was one critical issue on which Bobby Sands differed from other members of the IRA or Sinn Fein, and that was his view on electoral politics.

Sands believed that every available means had to be used to build their movement to "smash H block," including running a campaign for elected office. This put him at odds with Sinn Fein leadership, which, as we have seen, participated in the conventional political process only to the extent that they could express their belief in the illegitimacy of Westminster in the government of the Irish people.

Sands embrace of every means necessary also made him willing to commit to the most extreme form of civil disobedience. When Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams pleaded with Sands to not start the second wave of hunger strikes, Sands was not swayed. (Ross, p.114)

As I mentioned earlier, the hunger strikes were planned and coordinated for maximum effect.

But the chance to run for a seat in Parliament was fortuitous.

The sudden death of MP Frank Maguire offered an ideal opportunity to strike an embarrassing blow against the British establishment. Even for those opposed to the hunger strike and averse to political participation, the idea of placing Bobby Sands on the ballot proved irresistible. It would raise even greater public awareness for their cause.

Exactly who came up with the idea to run Sands is the subject of debate. Bernadette Devlin maintains that the first person to make the suggestion was a member of the Anti H-Block committee named Patsy O'Neill. O'Neil's original plan, which pre-dated Maguire's death, was to force the current MP to retire in order to make his seat available. (Ross, p.118)

Whatever debt is owed to Patsy O'Neil, it is abundantly evident that his plan would never have gotten off the ground were it not for the efforts of Devlin herself.

It was Devlin who had already organized local H-block/Armagh groups in every county in Ireland. (Ross, p.110). Even before McGuire's death, she had set up the organizational structure for a campaign such the one that would be used for Bobby Sands.

Devlin's contributions to the cause did not go unnoticed – including by the Unionists.

On January 16th, a month and a half before the Sands campaign started, a Unionist vigilante shot Devlin shot three times in her own home in front of her three small children. British soldiers, who had been stationed near Devlin's home to monitor her activities, did not intervene when the attack took place. Miraculously, Devlin survived.

Five days later, the IRA retaliated for the attack on Devlin by assassinating a unionist politician named Norman Stronge and his son.

The Anti H-Block committee called upon their supporters to remain nonviolent and they denounced the revenge killings. But it was hard to control the frustration and anger that many were feeling.

An indication of the rising temperature can be seen in an IRA a statement released at the time. It warned the British to "call off their dogs" and threatened to deal not only "with the dogs but also with their masters." (Ross, p.112)

A month after getting shot, Bernadette Devlin, had recovered enough to attend the funeral services for Frank McGuire. While there, she hinted to the Irish Times that she was considering running for McGuire's seat. This, in fact, was not her intention at all, as she was already plotting to have Bobby Sands put forward as the candidate. The idea of running herself was just a backup plan in case the Sands campaign fell through.

One early potential obstacle was Frank Maguire's brother, Noel, who expressed an interest in running for his brother's former seat – a move which would have split the vote. Once the idea of Sands' campaign was put forward, and Noel was informed that it was "the only way of saving Bobby Sands' life.," the other Maguire graciously backed down. (Ross, p.121)

Another real concern for the Anti H-block committee was the unpreparedness of the ordinary people of Fermanagh and South Tyrone. After so many years of abstentionism, there were fears that the voters could not be mobilized in time. The committee even assumed that they would need to send a party expert from Belfast to give local organizers a crash course in electoral politics.

What they discovered, to their delighted amazement, was that the Catholic population in Fermanagh and South Tyrone had almost secretly been preparing for just such an election. Despite the longstanding militant Republican rejection of electoral politics, the Catholics of the local constituency were registered, organized, and already trained to run a campaign. Almost from the shadows, they had infiltrated institutional positions from which they could also supervise the count to make sure the results were fair. They had even carried out a successful campaign to thwart British efforts to conduct a potentially subversive census before the election. "Don't return it – burn it," they urged their neighbors when receiving census notices in the mail. As one Anti H-Block Committee leader recalled "They were brilliant". (Ross, p.120)

The stage was set for the campaign of Bobby Sands for the a seat in the legislative body of the government that currently held him prisoner.

Sands himself characterized his campaign in terms that placed it beyond his own individual struggle. It was, as he put it, a fight for "the right of human dignity for Irish men and women who are imprisoned for taking part in this period of the historic struggle for Irish independence." Clearly, he saw his campaign as part of an 800-year-long battle against British dominion over Ireland.

But there is no question that the galvanizing force behind his win was sympathy for his personal pain and struggle.

It goes without saying that both incarceration and physical incapacity prevented Sands from campaigning on his own behalf. At this stage in the hunger strike, he could barely move as starvation eroded his strength and ability to function. But the working class people of Fermanagh and South Tyrone, as well as organizers of the Anti H-Block committee, carried his message to voters and led to his surprising victory.

On April 9th, 1981, Bobby Sands defeated Unionist Harry West by 1,500 votes.

Sands was now a prisoner, a registered terrorist, and a member of the British parliament. More importantly, with the Anti H-Block movement, he had proven that he had the people behind him.

Part 4: The Ten Martyrs

As much as Thatcher tried to downplay Sands' achievement, the victory was a massive embarrassment for the Tory government, who found it harder and harder to escape the attention of international leaders to the Troubles of Northern Ireland.

After three Irish ministers to the European Parliament met with Bobby Sands during his hunger strike, they requested an urgent meeting with the Thatcher government. Thatcher retreated beneath the flimsiest of diplomatic covers; she bluntly replied: "it is not my habit or custom to meet MPs from a foreign country about a citizen of the United Kingdom." (Ross, p.129)

Her pretext was as petty as it was insulting. All of a sudden, Ireland had become a "foreign" place for the English, not to mention the rejection of EU ministers as outsiders with no say in matters of human rights in the UK.

Among other visitors to Bobby Sands during his hunger strike was a Labour Party Spokesperson from Northern Ireland, who, after the visit, promised support on the criminalization issue if their party was to take government. Labour, of course, did not come to power again for many years, but this show of support was yet another indication that the prisoners' petition may have been more effective if directed at a government with a conscience.

In other words, had it not been for Thatcher's government, the protest might have succeeded.

On April 27th, a few weeks after Bobby Sands' victory, the Ulster police carried out a massive sweep of the homes of the Anti H-Block committee members. The committee afterwards released a statement to its supporters, "to continue in a peaceful manner and in such a fashion so as not to alienate the local community." (Ross, p.130) Thatcher had tried, but could not break their will.

But the people had their limit. And they would soon reach the point where calls for non-violence from the Anti H-Block Committee did no good.

On May 5th, sixty six days into his hunger strike and just a few weeks after winning a seat in Parliament, Bobby Sands died.

As soon as his death was announced at 1:30 am, Irish ghettos across Northern Ireland descended into chaos and rioting. People rang sirens, banged trash cans, and made sure their cries were loud enough for the rest of the world to hear. Even south of the border in the city of Dublin, so many protestors flooded the streets that the Irish army had to be placed on standby. (Ross, p.133)

No fewer than 100,000 people attended Bobby Sands' funeral. It was "the biggest IRA funeral since that of Terence MacSwiney in 1920." (Ross, p.132) MacSwiney, you will recall, was the Sinn Fein member whose death by hunger strike first brought international attention to the Irish struggle for independence.

Sands had now joined the pantheon of Irish martyrs who had died of starvation at the hands of the British.

Perhaps the failure of the first hunger strike, which left no one dead, intensified the shock created when one man actually carried out this terrible ordeal to the very end. But the anger and upset were also rooted a painful history. Almost every Irish person living in Ireland today is descended from a survivor of the Great Potato Famine. The same can be said for much of the Irish disporia in the U.S., Canada and Australia. Bobby Sands' protest against the British addressed the whole of the historical injustice against Ireland and it was conveyed in an action that resonated within the collective memory of that past. This is how the movement went from a few radical demonstrators at its beginning to crowd of 100,000 people crying in the streets.

The hunger strike was far from over. Nine other prisoners in H-block followed Bobby Sands.

And the Anti H-Block Committee, to keep the momentum going, ran even more prisoners as candidates.

Socialist groups like Popular Democracy and others associated with the movement performed well in subsequent city council elections in Northern Ireland.

Owen Carron, a Republican nationalist, would also win back Bobby Sands' seat after his death in Fermanagh and South Tyrone with even wider margins. The Anti H-Block committee even ran candidates in the Republic of Ireland. On June 11th, two Anti H-Block prisoners, Kieran Doherty and Paddy Agnew, won seats in the Irish Dáil. (Kieran would last 73 days on hunger strike).

But after Joe McDonnell, the fifth hunger striker to die, the movement had to face a disturbing realization. While it was true that they were having modest electoral success and despite earning the highest levels of public support since Bloody Sunday, the Anti- H Block movement had to concede that the Unionist establishment and the British government were still not budging at all.

It got worse as the sixth hunger striker, Martin Hurson, was nearing his own death a week after McDonnell's. By then the public was well aware of the excruciating pain experienced by the hunger strikers in their final days, when even the slightest sound could increase the agony. Capitalizing on this, unionist extremist groups known as Orangemen gathered (in a perverted vigil) outside of H block prison to loudly bang drums in order to torture the dying prisoner.(Ross, p.139)

From the heartless cruelty of the Orangemen we get a sense of the angry reaction that the hunger strike elicited from the Unionist side. This anger translated into votes. And, as a result, the far-right of the Unionist wing was able to gain as much traction with its base as the Catholic Republicans were able to do with theirs. The hunger strikers were clearly not "melting the hearts" of their opponents. They were, in fact, making them even more extreme in their determination to maintain Unionist and Protestant domination over Northern Ireland.

After the youngest hunger striker, twenty three year old Thomas McElwee died, the Anti H-Block movement realized that their demands for political status would not be met no matter how many electoral victories they achieved.

On October 3rd, 1981, the hunger strike was called off. The Anti H-Block committee made their announcement late on a Saturday after the Sunday press had already gone out. It was a chagrined attempt to postpone and perhaps temper the glee they knew the news would be met with by the British media.

On October 6th, the British announced that all prisoners would be allowed to wear any clothes they wanted. This was not a concession to the prisoners' demands as it implied no recognition of the inmates as political prisoners. It was merely a bit of deflection and propaganda on the part of the British who would continue to masquerade the Troubles as a simple criminal issue.

All this was a quiet and anticlimactic ending for the Anti H-Block movement.

So now it is time to revisit the question asked at the beginning of the podcast: did Bobby Sands die in vain? To what degree did Sand's sacrifice have a positive impact for his cause? And why?

Let's begin with the legacy of the Anti H-Block Committee, as its members were, after all, the force behind Sands' campaign, if not the hunger strike itself.

Part 5: Conclusion

Although the Anti H-Block Committee disbanded, the two factions that that were most opposed to electoral campaign were, ironically, the groups that benefited the most: I am referring to the IRA and Sinn Fein.

Contrary to what most people might think, the IRA did not always enjoy strong support among Northern Ireland's Catholic population. In fact, the IRA were often mocked during the early period of the Troubles with a joke that claimed their acronym "IRA" stood for "I Ran Away."

In the months after the hunger strikes concluded, two of their mixed results led to a jump in IRA membership and terrorist activity. On the one hand, the failure of a non-violent campaign to sway British attitudes made more dispossessed Catholics willing to accept violence as a means to achieve their ends. At the same time, the elevation of one of their own to hero status – Sands had been, of course, an IRA volunteer – helped reestablished the credibility of the IRA.

This, in turn, seems to have emboldened the group to increase its militant activities. True to their pledge to deal "with their masters" if the British refused to "call off their dogs," the IRA would even come close to assassinating Margaret Thatcher in the Brighton hotel bombing of October 12, 1984.

The other faction that benefited greatly from the Sands' campaign was Sinn Fein.

Although Sinn Fein previously adhered to it traditional policy of boycotting elections, the Sands' campaign led them to make a complete 180 turnabout.

They were now determined to run candidates wherever and whenever they could. Although it was a slow evolution starting in 1981, Sinn Fein is now (in 2022) the most popular party in Northern Ireland.

The Bobby Sands' campaign had awakened them to the idea that electoral politics is worth it after all.

It is a shame, however, that this lesson was not learned before Bobby Sands began his hunger strike. As mentioned earlier, two MPs from Northern Ireland abstained when they might have saved a Labour government in 1979. If these ministers had voted differently, the hunger strikes might have been carried out under a more-conscientious Labour government, and this might have led to a different outcome.

After all, it was a Labour government led by Tony Blair that would eventually sign the Good Friday Agreement that finally put an end to the Troubles.

Following the aphoristic declaration of Kwame Ture, I have maintained throughout this episode that Margaret Thatcher's cold ruthlessness was the major reason for the failure of Sands' martyrdom to change British policy. However, the blame can also be shared by the United States and the European community as well.

Throughout the hunger strike, Anti H-Block Committee spokespeople – from Bernadette Devlin to the first "blanket man" Kieran Nugent – toured North America and European countries in an appeal for solidarity.

The response fell short of expectations.

Although modeled after the American Civil Rights movement, the effort to smash H Block and garner international support for the oppressed Catholics of Northern Ireland was hampered by a key difference in their respective circumstances.

Though less obvious, this difference helps explain how the earlier movement in the U.S. succeeded in its goals while the Civil Rights movement in Northern Ireland disintegrated into recurring violence.

One of the key reasons why the American Civil Rights movement succeeded was the Cold War and the corollary desire of the liberal establishment in the U.S. government to placate to foreign critics. It was well understood in American intellectual and political circles that images of black people getting lynched or bitten by police dogs provided the Soviets with a rich source of anti-Western propaganda. This was not only an embarrassment. At a time when the Soviets were trying to lure newly independent countries into their sphere of influence, it was a matter of national security.

As much as it was a moral blight, the condition of African Americans in the segregated South (and elsewhere) was a weak spot for the American political establishment.

Moreover, the leaders of the civil rights movement in the U.S. were well aware of this perception of vulnerability and they deliberately tried to exploit it to their advantage. Civil Rights figures like James Farmer, WEB Du Bois, James Baldwin in "the Fire Next Time," as well as former Attorney General Robert Kennedy and Secretary of State Dean Rusk, have all commented that civil rights legislation needed to pass to placate international critics and "hostile propaganda" from the Cold War. (Dudziak, p.185)

Many historians now understand that the dynamics of the Cold War was crucial for the American Civil Rights movement to "embarrass" the country, and to put enough international pressure on the U.S. (particularly its more liberal factions) to force a change in its policy.

But the Northern Ireland Civil Rights movement did not have the benefit of a geo-political conflict like the Cold War to leverage in its favor. It was impossible to alarm leaders in the U.S. and elsewhere into taking action to pressure the British.

Not only that. The civil rights movement in Northern Ireland was also hindered by the indispensable involvement of radical Marxists and socialists. One can well imagine their odds of persuading a conservative hawk like Regan.

Though it did not fully succeed in its stated short or long term goals, we can say at the very least that the Bobby Sands campaign was successful in revitalizing the Republican cause in Northern Ireland

And it did show once-adamant abstentionists that electoral politics had its proper place in a protest movement. These may seem like modest victories, given the scale of the sacrifice.

But there is an important lesson to be learned.

What organizers today can learn from Bobby Sands is that there is no reason why one shouldn't use every means available to popularize a cause. And that includes electoral politics.

Certainly the hunger strike was a bold and dramatic course of action, but we must acknowledge the role the campaign for the British legislature had in elevating the protest. It was the combination of the two that strengthened the movement and brought nearly a sixth of the Catholic population of Ireland into the streets in only a few months.

Many radicals on the Left in the U.S. dismiss electoral politics, usually because they deem the two major political parties to be illegitimate, with no real intention to advocate for working class interests. It is a principled stance not to be complicit in a corrupt system.

But it was exactly the same sort of unbending commitment that led Sinn Fein and other Irish Republicans to squander critical opportunities to advance their cause – to abstain or boycott on principle when their votes could have been decisive.

Bobby Sands understood that winning by any means was a far better way to advance one's cause than a misguided preference for ideological purity. Results trump the urge to spare oneself from the taint of a toxic political process. Electoral politics does not make one any less radical.

Finally, to answer the difficult question we first posed at the beginning of this episode: did Bobby Sands die in vain?

Judged only from immediate and tangible goals, then the answer is yes.

The deaths of Bobby Sands and nine others failed to win any concessions from the British.

Furthermore, by exposing the heartlessness of lawmakers in London and the cruelty of their Protestant neighbors, the non-violent hunger strike led to an exacerbation of violence, which was surely not what they wanted.

But there were intangible and more enduring changes brought about by Bobby Sands and his campaign.

When judged by these standards, then we must say that Bobby Sands and the others did not die in vain.

To reach this conclusion, we must view Bobby Sands' martyrdom from a perspective greater in scale than a few limited political concessions.

There is no better way for us to gain this perspective than through Bobby Sands in his own words.

As I mentioned, Sands was a writer and a poet. His writings have been meticulously archived by the Bobby Sands Trust.

One of the selections we can read on their website is a poem Sands composed before his death. It is titled "The Rhythm of Time" and is worth quoting in its entirety.

From the vantage point of a million years, Sands poem chronicles history's heroes in the struggle against injustice. Composed by a man wracked by the agonizing pangs of starvation and the approach of death, it is an unmistakable affirmation of hope and confidence in the justice of his cause.

As we read his poem, notice how Sands situates his battle and sacrifice within a centuries-long tradition of courage and selfless dedication to a righteous purpose. His is a struggle that goes beyond Ireland's 800-year conflict with the British. It claims fellowship with all those who have stood up for what is right and were willing to pay the ultimate price.

Sands' own words provide the answer we are seeking. His death was hardly a tragic failure.

It was a timeless victory for hope.

"The Rhythm of Time"

by Bobby Sands

There's an inner thing in every man,

Do you know this thing my friend?

It has withstood the blows of a million years,

And will do so to the end.

It was born when time did not exist,

And it grew up out of life,

It cut down evil's strangling vines,

Like a slashing searing knife.

It lit fires when fires were not,

And burnt the mind of man,

Tempering leadened hearts to steel,

From the time that time began.

It wept by the waters of Babylon,

And when all men were a loss,

It screeched in writhing agony,

And it hung bleeding from the Cross.

It died in Rome by lion and sword,

And in defiant cruel array,

When the deathly word was 'Spartacus'

Along the Appian Way.

It marched with Wat the Tyler's poor,

And frightened lord and king,

And it was emblazoned in their deathly stare,

As e'er a living thing.

It smiled in holy innocence,

Before conquistadors of old,

So meek and tame and unaware,

Of the deathly power of gold.

It burst forth through pitiful Paris streets,

And stormed the old Bastille,

And marched upon the serpent's head,

And crushed it 'neath its heel.

It died in blood on Buffalo Plains,

And starved by moons of rain,

Its heart was buried in Wounded Knee,

But it will come to rise again.

It screamed aloud by Kerry lakes,

As it was knelt upon the ground,

And it died in great defiance,

As they coldly shot it down.

It is found in every light of hope,

It knows no bounds nor space

It has risen in red and black and white,

It is there in every race.

It lies in the hearts of heroes dead,

It screams in tyrants' eyes,

It has reached the peak of mountains high,

It comes searing 'cross the skies.

It lights the dark of this prison cell,

It thunders forth its might,

It is 'the undauntable thought', my friend,

That thought that says 'I'm right!'

*Please note that inconsistencies between the above transcript and the actual recording are inevitable (though hopefully slight).